History and Development of ASTM E1007, Standard Test Method for Field Measurement of Tapping Machine Impact Sound Transmission Through Floor-Ceiling Assemblies and Associated Support Structures

By Wayland Dong, Acoustician, Westside Acoustics

By the 1960’s, multifamily housing in the United States was in the unhappy situation of large and increasing numbers of complaints of sound isolation [1], without even a defined method to measure, much less design or enforce, the sound isolation of separating walls and floor-ceiling assemblies. Despite a generally higher standard of living, especially in those immediate post-war years, the USA trailed far behind most countries in Europe in developing sound isolation methods and building codes [2], a lamentable condition that in many ways continues to the present. Since “it is better to adopt an approximate answer today than to wait 10 or 20 years for the perfect answer based on the necessary research” [2], the expeditious solution was undertaken to borrow European means and methods for measuring impact sound insulation.

The measurement method was based on the German DIN 4109 standard [3], [4], which was first published in 1938 as DIN 4110 [5] and was also the basis of ISO recommendation R140, which became today’s standards 10140 and 16283. The impact source is what we now refer to as the standard tapping machine, which drops five cylindrical steel hammers spaced 100 mm apart on the floor from a height of 40 mm. The hammers are 30 mm in diameter and weigh 500 g with a slightly curved impact face and drop sequentially at an overall rate of 10 Hz. The spatial- and time-averaged sound pressure level generated by the operation of the tapping machine on the source floor is measured in the receiving room.

Figure 1: Early examples of tapping machines at the Center for Acoustic and Thermal Building Physics at the University of Applied Sciences in Stuttgart, Germany. Dates of construction are not known.

The standard tapping machine was adopted as the impact sound source and formed the basis of Impact Insulation Class (IIC) published by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in a Guide in 1967 [6]. The test method was described only as “currently at use at the National Bureau of Standards” but eventually became ASTM E492. No explicit mention was made of a field test version of the standard, although many of the floor-ceiling assemblies in the FHA guide note that the data was obtained from field testing. Clearly, field testing of impact noise isolation using a similar method to what became E1007 was being performed for decades, but the formal test method was not published until 1984.

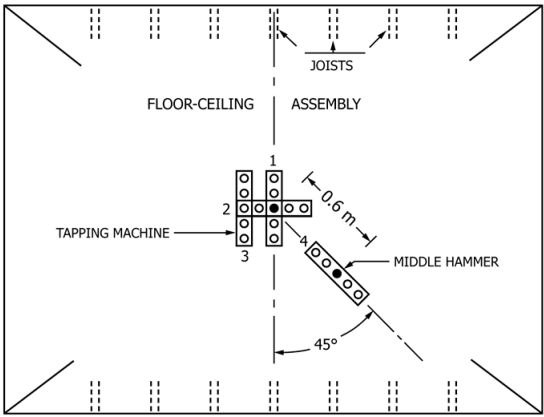

The method described in the FHA Guide averages the impact sound pressure level (ISPL) over time and space in the 16 third-octave bands from 100 – 3150 Hz using 6 stationary positions or a slowly moving microphone, which is similar to the current E1007. The tapping machine is to be placed in “at least three specified locations on the floor.” These locations were not specified in that document, but they were standardized in ASTM E492 as four tapping positions, all near the center of the room (see figure). The positions are clearly intended to excite the floor both on and between joists, and in several orientations, but the precise rationale for these positions has not been published. The standard does not distinguish between reflections or rotations of the positions, and therefore, the set of four tapper positions is not uniquely determined.

Figure 2: Definitions of the four tapping machine positions in ASTM E492 and E1007

E1007 uses the same positions as the laboratory test. Floors in the field can be much larger than the roughly 10 m2 of the laboratory specimen, so that the distance from the center of the floor to measurement points can vary considerably, but no consideration is given to the size of the rooms. By comparison, ISO 16283 specifies random tapper positions throughout the floor and increases the recommended number of tapper positions as the floor size increases.

This is typical of the early versions of E1007 in that it appears to be making as few changes as possible to the method in E492. In addition to the same source, source positions, and sound measurement method, it used the same interrupted noise method of measuring the decay in the receiving room and the same calculation method of , the normalized ISPL:

(1)

where is the average SPL in the receiving space,

is the calculated absorption in the receiving space per ASTM E2235, and

is the reference amount of absorption of 10 m2. This reference absorption level is the same as the laboratory test, the importance of which is discussed below.

The name of the classification rating originally defined in the standard, Field Impact Insulation Class (FIIC), clearly indicates the minimal changes between it and the laboratory rating, IIC. The name is also in parallel with Field Sound Transmission Class (FSTC) defined in the contemporary version of E336.

Normalization

The normalization in Eq. (1) was intended to allow comparison of results from receiving rooms with differing amounts of absorption. There were two versions of the normalization procedure in the existing standards of the time, either to a standard amount of absorption (10 m2) or a standard reverberation time (0.5 second). The 1963 FHA document used reverberation time normalization to avoid the necessity of calculating the volume of the receiving room [3], but by the 1967 FHA guide, only normalization to absorption was included [6]. The airborne sound isolation standard, E336, included ratings with both normalization methods since 1977, but E1007 only included the absorption option. At any rate, it was generally believed that the two methods were “equivalent and comparable” [3].

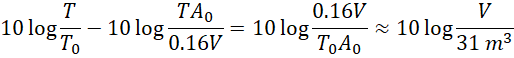

Explicitly, since the absorption is calculated from the Sabine formula, , where V is the volume of the receiving room and T2 is the measured reverberation time, the difference between the methods is

so that the difference in normalization methods depends entirely on the receiving room volume. The difference vanishes for receiving room volumes of about 31 m3 or 1100 cu. ft. The fact that the typical amount of absorption in a reverberation chamber (10 m2) is approximately what is required to achieve a reverberation time of 0.5 second in a small room is an unfortunate coincidence, which misled many to assume that these normalization methods were “equivalent and comparable.”

Schultz states that “for the typical range of room volumes” (about 22 – 60 m3, 775 – 2100 cu. ft.) the difference (-1.5 to +2.8 dB) was “no greater than the uncertainty of typical field measurements” and was therefore not consequential [3]. There is no source given for the range of room volumes, but it was presumably based on the available test data. When this exercise is repeated for more modern testing, the 90th percentile receiving room volume was 110 m3 (3885 cu. ft.) with a resultant difference of 5.5 dB [7]. This is nearly twice what it was in the 1960’s and clearly too large to be ignored. The normalization method in Eq. (1) penalizes large rooms by demanding an unreasonably small amount of absorption; for a 110 m3 room, the sound level is effectively normalized to a reverberation time of 1.75 seconds!

The issues with absorption normalization were identified in a paper published in 2005 [8] with a resultant major revision to the standard in 2011. In addition to the existing absorption normalized ISPL (ANISPL), reverberation time normalized ISPL and non-normalized ISPL were added to the standard. These became the basis for new single number ratings, Normalized Impact Sound Rating (NISR) and Impact Sound Rating (ISR), respectively, parallel to NNIC and NIC in E336. Field IIC (FIIC) was renamed Apparent IIC (AIIC) in recognition of the presence of flanking paths and to parallel ASTC defined in E336.

It is not often recognized that the absorption normalized ratings like AIIC are measurements of apparent sound power (the performance of the separating assembly), whereas the reverberation normalized ratings (NISR) are measurements of sound pressure (sound isolation between any two spaces). Sound power measurements require significant constraints such as limited receiving room absorption, well defined specimens and rooms, and accurate determination of receiving room volumes. The resultant level is of limited use because the sound from flanking paths is attributed to the specimen. By contrast, the sound pressure measurement is indicative of the sound environment experienced by an occupant and is therefore the preferred measurement. The International Building Code section 1206, which is the basis of sound isolation code requirements in most jurisdictions in the United States, now explicitly requires NISR/NNIC be used for the evaluation of sound isolation between residences in the field [9]. In the author’s opinion, AIIC is at best redundant with NISR and one day may be removed from the standard.

Lateral measurements

Even in early versions of the standard (at least to 1997), the standard said the receiving room was “located beneath or adjacent to the floor specimen under test,” although this is somewhat contrary to the use of absorption normalization as described above. The situation was clarified with the 2011 revision, when AIIC was specified to apply only to the receiving space directly below the tapping machine, while ISR/NISR could be measured in any space. However, the location of the tapping machine is not adjusted, and the center of the floor is a varying and potentially large distance from a laterally adjacent room.

For this reason, a modified method has been proposed for lateral or diagonal adjacencies (i.e., receiving rooms that share a junction with the source floor) in which the tapping machine is at a fixed distance of 5 feet or 1.5 m from the separating junction [10], [11], [12]. This revision may be adopted in future versions of the standard.

Volume requirements

Early versions of the standard defined acceptably diffuse sound fields as requiring minimum volumes of 60 m3 at 100 Hz, 40 m3 at 125 Hz, and 25 m3 at 160 Hz, and required the report to note where this requirement was not met. As noted above, this applied only to FIIC (AIIC).

In 2011, AIIC was limited to receiving rooms of at least 40 m3 with a 2.3 m minimum dimension and absorption less than 2 V2/3. NISR was permitted for receiving rooms up to 150 m3. No reason for the upper limit is given, although it is parallel with E336, where a similar requirement exists. No lower volume limit exists for NISR, although this is a matter of current discussion.

In 2014, additional requirements for coupled receiving spaces were added for AIIC measurement, required volume weighted SPL measurements. As discussed above, such care in defining the volumes for calculation of the absorption are required for sound power calculations but is ultimately of little use. The method could be significantly simplified without detriment if the AIIC rating were removed.

ASTM Committees

ASTM membership is low-cost, and the committees are open to all interested parties. All researchers and consultants working in the field of sound insulation are invited to join ASTM and participate in the discussions of future revisions of this standard.

References

[1] F. P. Rose, “Owner’s Viewpoint in Residential Acoustical Control,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 740–742, Apr. 1964, doi: 10.1121/1.1919057.

[2] O. Brandt, “European Experience with Sound-Insulation Requirements,” J Acoust Soc Am, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 719–724, 1964.

[3] T. J. Schultz, “Impact-Noise Recommendations for the FHA,” J Acoust Soc Am, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 729–739, 1964.

[4] T. Mariner and H. W. Hehmann, “Impact-Noise Rating of Various Floors,” J Acoust Soc Am, vol. 41, no. 1, p. 206, 1967, doi: 10.1121/1.1910319.

[5] M. Schneider and H.-M. Fischer, “German Standard DIN 4109 (Sound Insulation in Buildings) in the Context of Technical, Scientific and Social Developments,” in Proceedings of the 10th Convention of the European Acoustics Association Forum Acusticum 2023, Turin, Italy: European Acoustics Association, Jan. 2024, pp. 2849–2856. doi: 10.61782/fa.2023.0065.

[6] R. D. Berendt, G. E. Winzer, and C. Burroughs, “A Guide to Airborne, Impact, and Structure Borne Noise–Control in Multifamily Dwellings.,” 1967.

[7] W. Dong, J. Lo Verde, and S. Rawlings, “Sound pressure-based ratings are preferred for evaluation of insitu sound isolation,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 151, no. 4_Supplement, p. A34, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.1121/10.0010572.

[8] J. J. LoVerde and W. Dong, “Field impact insulation testing: Inadequacy of existing normalization methods and proposal for new ratings analogous to those for airborne noise reduction,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 118, no. 2, pp. 638–646, Aug. 2005, doi: 10.1121/1.1946267.

[9] S. Rawlings, J. Lo Verde, and W. Dong, “The use and application of pressure-based acoustical metrics adopted within the International Building Code,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 152, no. 4_Supplement, p. A66, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1121/10.0015562.

[10] J. LoVerde and W. Dong, “Measurement of Lateral Impact Noise Isolation,” in Proc ICSV24, London, England, UK, 2017.

[11] J. LoVerde and W. Dong, “Measurement and evaluation of lateral impact noise isolation,” INTER-NOISE NOISE-CON Congr. Conf. Proc., vol. 259, no. 5, pp. 4827–4833, Sept. 2019.

[12] J. Lo Verde, W. Dong, and S. Rawlings, “Lateral impact noise II: Practice and recommended procedures,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 152, no. 4, p. A66, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1121/10.0015560.

About the author:

Wayland Dong has focused much of his career as an acoustical consultant on advancing the science and practice of impact sound insulation in multifamily dwellings. In addition to the work on normalization methods and lateral impact transmission mentioned in this article, he and coauthor John LoVerde have developed a two-rating method of measuring impact sound isolation in which the low and high-frequency components of impact sound are evaluated independently, which has been implemented as new ASTM ratings. He is currently an Acoustician at Westside Acoustics, a consulting firm in Los Angeles.