Evaluation of Dublin Airport’s Noise Pollution

By St. Margarets The Ward/FORUM

Dublin Airport in Ireland opened a new parallel runway, the North Runway, in August 2022. The runway opened following many decades of planning and regulatory approval. However, what became apparent to the communities of North County Dublin and neighboring County Meath was that flight paths for departures using the North Runway were in the wrong place. Thousands of homes that should never have been exposed to significant levels of aircraft noise were now severely impacted.

Quickly, resident groups in the affected areas became active. St Margarets The Ward (SMTW) and Fingal Organised Residents United Movement (FORUM) groups began to petition authorities to investigate the operations from Dublin Airport. They turned to Fingal County Council (FCC) the local authority and the Airport Noise Competent Authority (ANCA) for help and answers.

To date, investigations into flight paths at Dublin Airport by authorities remain ongoing. However, the SMTW and FORMUM groups have taken the initiative to fund their investigation into the noise effects. This article offers a viewpoint on the noise evaluations carried out by airport authorities, focusing on the experiences of communities directly affected by the noise. It will compare measurements to modelled scenarios, discuss how noise is averaged by airport authorities compared to the individual events that communities hear, discuss how regulations are stacked in favor of the airport operators and conclude with some suggestions that would improve the engagement of communities by airport authorities in future.

History of the North Runway

Dublin Airport is located north of Dublin City within the Fingal County administrative area. The airport first opened in 1940 with a grass runway. In 1950, a new concrete runway replaced the original grass runway, officially known as Runway 16/34. The first main runway (10/28) was opened in 1989, this is often referred to as the South Runway.

The North Runway concept has been discussed for decades; however, it wasn’t until 2004 that a planning application was submitted by the airport operator to the local planning authority. After considerable debate and a full public planning hearing, the runway eventually was granted permission in 2007 with a series of conditions attached. Many of the conditions related to environmental protection include noise protection for local communities.

Due to the economic downturn in 2008, the runway construction was put on hold until 2016. At that time, some of the environmental protection conditions had to be implemented including insulation of homes and schools. The eligibility for these schemes was based on a series of noise contours which were, of course, based on a set of flight paths – ones that communities around Dublin Airport fully expected to be delivered when the runway opened.

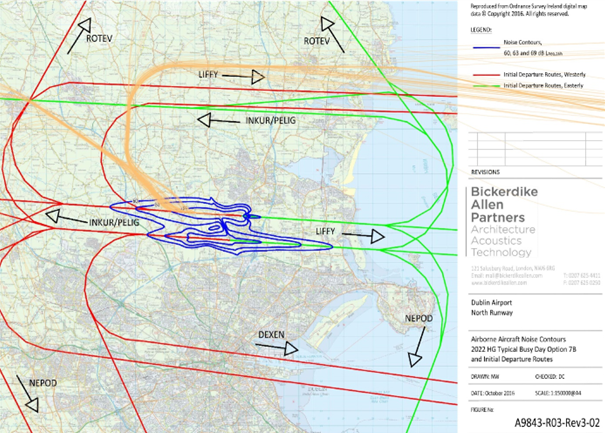

Following construction of the runway, the first flight departed on 24 August 2022. However, the flight path for this flight and every flight was completely different from the paths that were permitted by the planning application and that the community expected. To illustrate this, Figure 01 overlays the flight paths now in use at Dublin Airport in orange, on the noise insulation eligibility contours, and the flight paths, in red and green, used to create them in 2016.

Figure 01: Actual Flight Paths Compared to Permitted Flight Paths

The flight paths being used today turn sharply at low altitudes and fly over many areas that never expected to be under a flight path. This includes nursing homes, sports clubs, schools, pre-schools, villages, and towns.

No consultation was ever given to present this new flight path to communities who experienced the reality of noise from aircraft at low altitudes instantly with the opening of the North Runway.

Aircraft Noise Contours – The Community Perspective

Residents living close to Dublin Airport were acutely aware of the North Runway development long before it was built. For several generations, the North Runway project and its associated noise impact was studied closely by families before making decisions to settle in the area. This was done in the main by reviewing noise contour maps which graphically illustrate the expected noise level for airport operations.

We’ve faced several challenges comparing noise contour maps with real airport noise levels. A key issue is the averaging methodologies used by airports to create these maps, often resulting in lower noise levels depicted than what is heard from actual aircraft flyovers.

Noise contours are presented in terms of a variety of metrics, but the most common ones are LAeq,T, Lden and Lnight. Each of these metrics are average noise levels usually presented either over a specified modelling period of 92 days in the case of LAeq,T , or over a full year in the case of Lden and Lnight. Aircraft noise by its nature is an intermittent noise source that results in high noise levels when an aircraft is overhead followed by periods of lower background noise in between flights. Therefore, averaging the noise over time reduces the reported noise level significantly. In the case of computer-generated noise contours, the quiet time between flyovers is treated as having zero noise. The zero noise periods are included in the averages, having the effect of reducing the average level over a specific period.

People don’t experience noise in this manner; the irritation caused by aircraft noise occurs at the moment of maximum noise from an aircraft passing overhead. Residents might use phone applications to measure noise levels, which although not scientifically precise, do provide a relatively accurate indication of the maximum noise produced by aircraft movements. It’s immensely frustrating for communities to measure maximum noise events exceeding 80dB, only to find from a contour map that the average noise level at their location is less than 60dB.

Moreover, noise contours not only average noise over time to show a lower figure but also incorporate a modal split to accommodate different wind conditions. For example, at Dublin Airport, the Dublin Airport Authority (DAA) states that 70% of the time, winds come from the west and 30% from the east. This additional averaging diminishes the noise level shown in contour maps for communities to the west and worsens the discrepancy for residents expecting the contour map’s noise level to match what they actually experience.

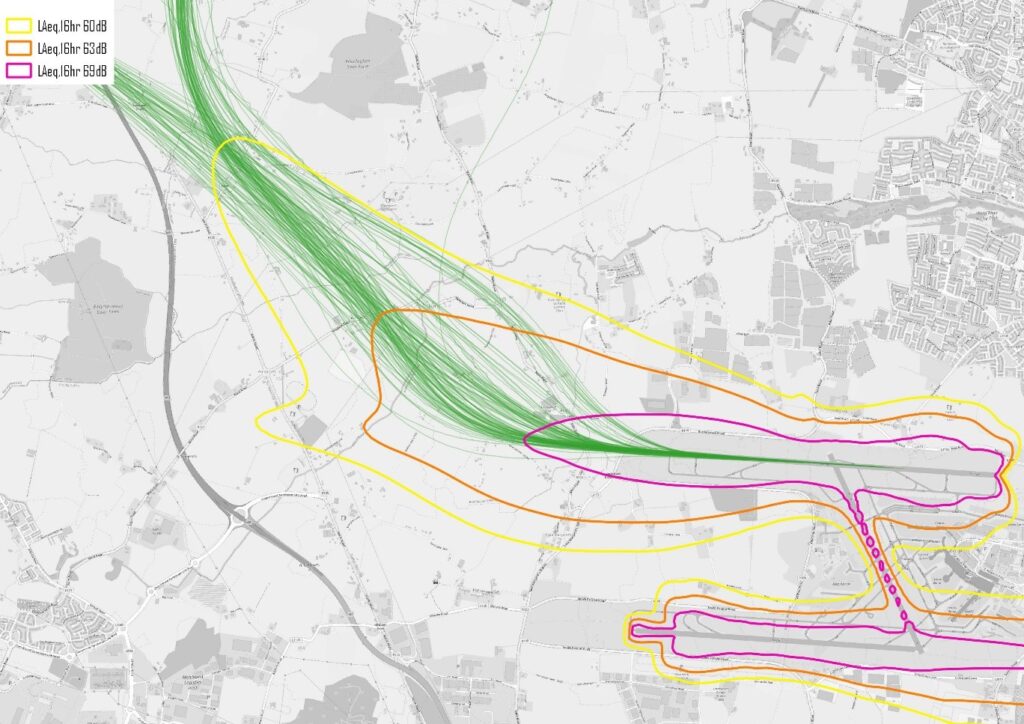

To demonstrate this using real data, our groups carried out noise monitoring during the summer of 2023. The monitoring was done using calibrated noise monitoring equipment and the data was analyzed and reported by a competent acoustic consultant. In addition to the monitoring done by our group at two locations (Locations A and B), DAA also had a noise monitor at a third location (Location C) in a local primary school, Kilcoskan NS. Figure 0-1 presents the locations of the noise monitors with westerly departure flight paths also indicated in green. Overlaid on the image are the noise contours for the Summer 2023 period produced by DAA.

Figure 01: Noise Monitoring Locations

When we examine the maximum instantaneous noise level of aircraft flyovers, the contrast between the contour maps and the actual noise level experienced by our communities during an aircraft event becomes evident. Table 01 summarises the typical measured maximum noise level from aircraft flyovers at each location to compare to the noise contour levels for the same location.

Table 01: Comparison of Maximum Noise Level Measurements to Noise Contours

| Location | Typical Measured Noise Level dB LASMax | Estimated Noise Contour Level dB LAeq,16hr | Difference, dB |

| Location A | 80 | ~67 | +13 |

| Location B | 78 | ~63 | +15 |

| Location C | 76 | ~60 | +16 |

Table 02 summarises the measured typical daytime average noise level at each location to compare to the noise contour levels for the same location.

Table 02: Comparison of Measurements to Noise Contours

| Location | Typical Measured Noise Level dB LAeq,16hr | Estimated Noise Contour Level dB LAeq,16hr | Difference, dB |

| Location A | 70 | ~67 | 3 |

| Location B | 66 | ~63 | 3 |

| Location C | 63 | ~60 | 3 |

The noise contour maps underestimate the noise levels for a typical day with departing flights overhead. Some of this is due to the averaging exercise that is carried out. It is also possible that the noise model that produces the contour maps is not sufficiently accurate or has not been correctly validated to account for the sharply turning flight paths.

In the case of Dublin Airport and North Runway departures, there are over 400 flights daily following the flight tracks depicted in Figure 01. For our communities, this means experiencing 400 or more individual maximum noise events daily, which are loud enough to disrupt outdoor conversations, necessitate an increase in TV and radio volume indoors, and require residents to keep windows closed to mitigate noise.

For communities, the noise contours commonly used by airport operators are too abstract. Instead, noise contours should be presented in terms of the maximum instantaneous noise level that a community could expect to hear. They should also be presented as single-mode contours which do not apply the averaging to account for the modal split discussed earlier.

This approach would provide a transparent representation of noise around the airport, offering communities the information they need, especially when the contours forecast future operations not yet implemented.

A Case Study in Poor Community Consultation

Effective consultation with communities is essential for any organization aiming to implement projects, or initiatives that directly impact those communities. However, when consultation processes are poorly executed or neglected altogether, the consequences can be severe. Not only does poor consultation undermine trust between stakeholders and decision-makers, but it also breeds animosity and resentment within the affected communities. Unfortunately, Dublin Airport is a case study in poor community consultation.

We’ve detailed how flight paths from the new North Runway at Dublin Airport haven’t met community expectations. Since the North Runway opened in August 2022 there have been over 53,000 individual complaints. Most noise complaints relate to departures from the North Runway using unauthorized flight paths. However, there’s a significant flaw with the complaints system: complaints are directed to Dublin Airport for investigation. The authority responsible for operating the airport is also the authority specified to investigate complaints. Neither the Fingal County Council nor the Airport Noise Competent Authority (ANCA) will accept noise complaints from communities.

To date, noise complaints haven’t prompted any review of the actual noise level by the authority. The only outcome of making a complaint is that the flight path flown is compared to an environmental corridor specified by the airport itself to match the unexpected flight paths. Complaints are routinely dismissed with a comment stating that the flight path is within the corridor, regardless of the noise generated.

Despite the significant anger and numerous complaints from affected communities, there has been no effort made towards transparent public consultation. Officials from DAA consistently decline to attend public town hall meetings, where local volunteer groups like ours endeavor to clarify the situation to our communities. Instead, the DAA prefers to rely on a Community Liaison Group (CLG), which, at best, appears to be a tokenistic attempt at engagement.

The CLG was set up to facilitate discussions between the DAA and community representatives regarding the impact of airport operations on nearby communities. However, since the opening of the North Runway, there has been a reluctance to address the primary concern of our communities: the North Runway flight paths. As a result, the CLG has evolved into mere token consultation, enabling the airport authority to assert that they engage with communities, when there is no sincere effort to listen to the concerns of the communities.

Inadequate consultation with communities carries extensive repercussions, ultimately resulting in the erosion of trust and the exacerbation of animosity. This is evident in the significant volume of objections from the public to any projects proposed by Dublin Airport; communities simply do not have confidence in the information contained within these plans.

The Balanced Approach – Who Does the Balance Favor?

EU law mandates the adoption of the “Balanced Approach” when evaluating potential operating restrictions at European Airports. This approach aims to implement aircraft noise management while considering the needs of both the aviation industry and the communities affected by aircraft noise. In theory, this seems reasonable; however, in practice, communities often find themselves confronted with a system designed to tilt the balance in favor of maximizing airport capacity.

The fundamental challenge lies in achieving aircraft noise control for communities near airports without implementing operating restrictions. However, the Balanced Approach positions operating restrictions as a last resort for noise management, prioritizing other measures instead. The four principal elements of the balanced approach to aircraft noise management are:

- Reduction of Noise at Source

- Land-Use Planning and Management

- Noise Abatement Operational Procedures

- Operating Restrictions on Aircraft.

Each of these are discussed in turn.

Reduction of Noise at Source

According to airport operators, quieter aircraft are seen as the solution. It’s undeniable that modern aircraft are quieter than previous generations of jets. However, any reductions in noise are overshadowed by the significant increase in the number of aircraft movements. This acknowledgment is even made by the International Civil Aviation Authority (ICAO) in their Working Paper on the Management of Noise (ICAO Document Reference A40-WP/260). They state,

“Aircraft technology has dramatically reduced the noise footprint of individual aircraft movements in past decades. However, in many areas, this progress in reducing aircraft noise at source has been challenged by global increases in traffic and the introduction of larger aircraft. It has also become more difficult to identify new ways of significantly improving the technical noise performance of aircraft. The result has been an increase in cumulative noise levels around some airports.”

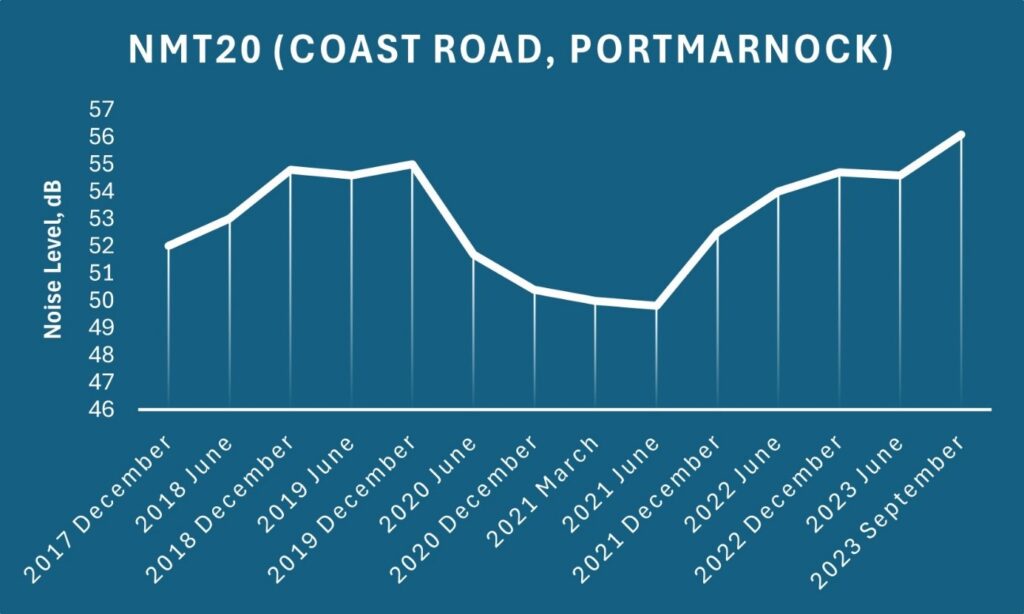

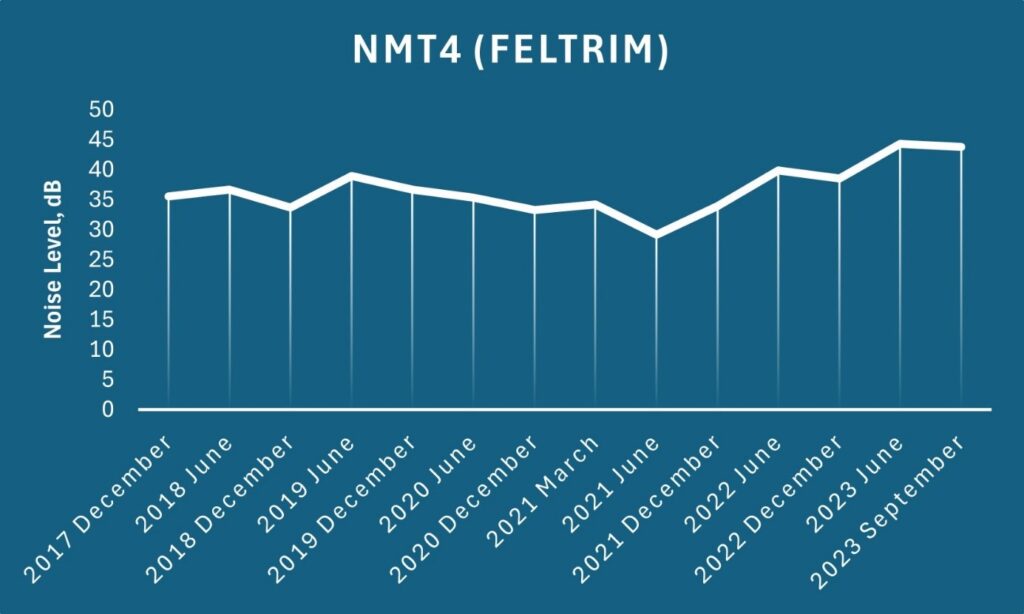

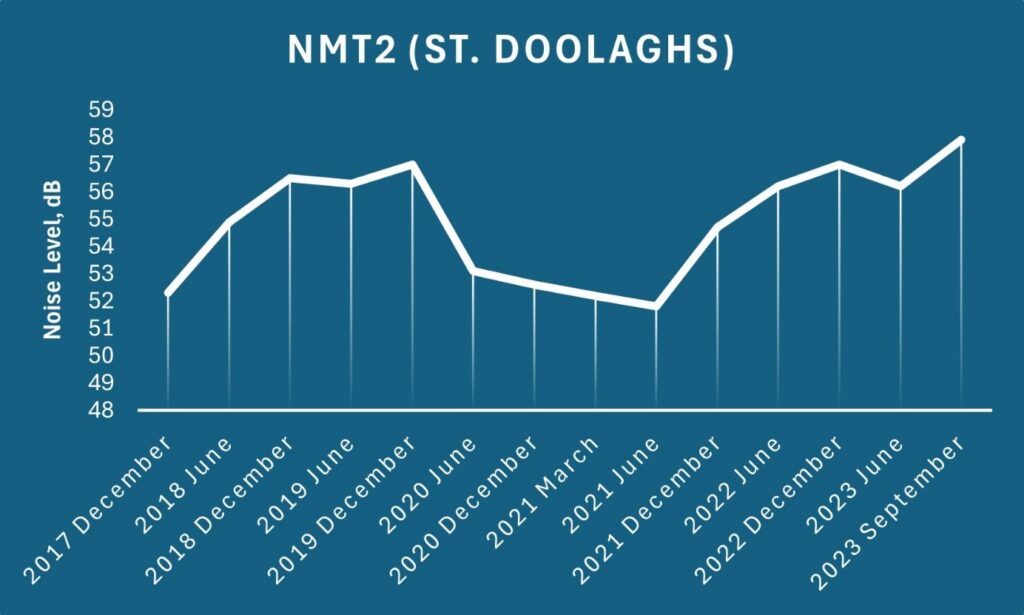

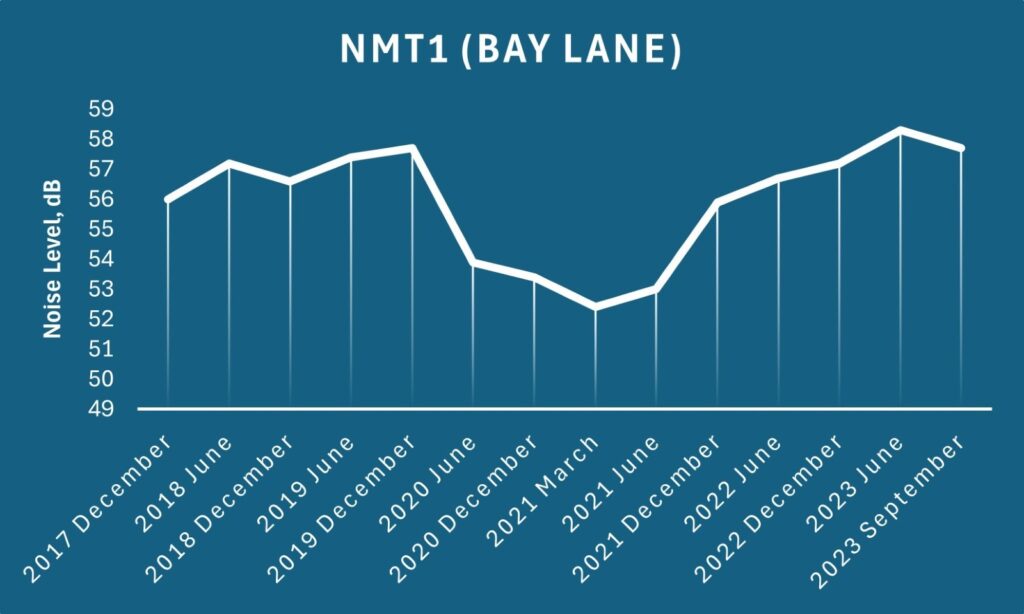

In summary, while individual aircraft may have become marginally quieter, the rise in air traffic volumes has led to no overall reduction in noise levels for communities surrounding airports. This holds for Dublin Airport and can be evidenced by the noise and flight track monitoring data available on the Dublin Airport website. The charts below illustrate the average night-time noise levels (LAeq,8hr) recorded by permanent noise monitors at the airport over time, spanning from 2017 to the present day. The noise figures are taken from regular reports issued by DAA1.

Figure 01: Summary of Noise Monitoring at NMT20

Figure 02: Summary of Noise Monitoring at NMT4

Figure 03: Summary of Noise Monitoring at NMT2

Figure 04: Summary of Noise Monitoring at NMT1

Each monitoring location depicts a consistent trend: noise levels measured in 2023 surpass those recorded in 2017 when monitoring commenced. The only notable reduction in noise occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2022.

The potential for future noise reductions at the source seems exceedingly limited without also constraining capacity. Nonetheless, Dublin Airport positions this strategy as central to its plans for noise reduction, although the evidence of how this will be accomplished remains far from compelling.

Land Use Planning and Management

This category includes noise zones where new residential development may be restricted, it includes noise insulation schemes, and also includes financial incentives to reduce airport charges for quieter aircraft for example.

Our community has experienced all of these management tools and they are ineffective at the very thing they are promoted to achieve, reducing aircraft noise.

Noise zones are established around Dublin Airport to restrict development, but unfortunately, they are based on hypothetical flight paths that are not currently in use. Consequently, many new homes have been constructed, and new families have settled in areas where, according to the noise zones, they had no noise concerns. However, the reality is that these areas are directly beneath flight paths. Additionally, the noise zones only apply to new developments; existing housing receives no benefit, and there is no reduction in noise by zoning the land around the airport.

Insulation is often proposed as a solution to mitigate aircraft noise. However, its effectiveness is limited to indoor spaces and relies on keeping windows and doors closed at all times. This lifestyle isn’t conducive to healthy living, as it confines people indoors and compromises the outdoor environment. Moreover, insulation can only provide partial relief, and for many homes, outdoor noise levels are so high that effective insulation is impractical. Additionally, insulation does not address the root issue of reducing noise pollution outdoors.

Ultimately, while the notion of offering financial incentives to encourage quieter aircraft to utilize an airport may seem appealing, our demonstration has revealed that the slight reduction in noise from modern aircraft is eclipsed by the surge in traffic. Consequently, the net outcome is not a decrease in noise, but rather an increase, as is the case with Dublin Airport.

The community’s view on land use planning and management is that it is fundamentally ineffective at reducing the noise level.

Noise Abatement Operational Procedures

While there is potential for noise abatement procedures to be advantageous, in the case of Dublin Airport, the authority to implement noise-reducing procedures rests solely with the airport operator. Regrettably, this has led to the unsatisfactory situation of having no noise abatement operational procedures in place at Dublin Airport.

Without independent oversight to implement these measures communities like ours are left to hope that airport operators will voluntarily introduce them.

Operating Restrictions

For communities, implementing operating restrictions to limit the overall number of flights appears to be the most impactful measure. However, within the framework of the balanced approach, it is considered the last resort. The balanced approach seems to serve as a methodology to enable airports to avoid implementing operating restrictions, rather than ever seriously considering their introduction.

For example, at Dublin Airport several operating restrictions are in place as part of the mitigation measures which allowed the North Runway and other airport developments to be granted permission. The restrictions in place at the moment are:

- The total number of night-time flights at Dublin Airport shall be limited to 65 per night, the night is defined as 23:00hrs to 07:00hrs

- The North Runway shall not be used at night between the hours of 23:00hrs and 07:00hrs

- The total number of passengers allowed at Dublin Airport is capped at 32 million per annum.

Although operating restrictions are intended to be enforced, in practice, they are not adhered to. In 2023, for instance, the average number of night flights stood at 115, with over 33 million passengers passing through Dublin Airport. Furthermore, the North Runway is frequently utilized at night for periods lasting 4-5 nights consecutively to facilitate maintenance work.

The DAA has pursued the removal of the 65-flight restriction and proposed its replacement with a noise quota system, which would permit unlimited night flights in the future. Additionally, they have sought to raise the passenger cap from 32 million to 40 million.

In essence, our communities are confronted with a situation where the balanced approach makes it arduous to introduce new operating restrictions, yet it provides a mechanism for existing restrictions to be lifted. This approach cannot genuinely be considered balanced, as it favors airport operators and airlines.

Conclusion

SMTW and FORUM remain steadfast in advocating for our communities against the excessive noise generated by Dublin Airport. Our core objective is to hold the authorities governing Dublin Airport accountable and to campaign for compliance with all existing planning conditions and restrictions that the airport is obligated to adhere to. These include:

- Flight paths used at the airport should be those that were used to assess the environmental impacts in the Environmental Impact Assessment submitted as part of the North Runway planning permission. Any other flight paths must be considered as unauthorized until they have been assessed and approved by the planning authority.

- Night-time flights at Dublin Airport are restricted to a maximum of 65 flights per night. However, this limit is frequently exceeded, prompting the local planning authority, Fingal County Council, to issue an enforcement order demanding compliance with this condition. The airport’s response has been to legally challenge the validity of the enforcement order and the condition itself. Our communities assert that the North Runway was only granted permission with the understanding that this night flight restriction would safeguard us from excessive nighttime noise. The night flight cap must remain in place.

- Expansion of Dublin Airport beyond 32 million passengers must not be entertained until the issues surrounding flight paths and night flight conditions are resolved. Without resolution, any further expansion is untenable. When expansion is contemplated, a comprehensive independent review of noise levels and mitigation measures surrounding the airport must be conducted. For our communities, the airport has proven to be a poor neighbor, and any expansion should only proceed if noise mitigation measures are maximized for affected areas. Dublin Airport should be operated with the most effective noise mitigation measures in place, considering the current understanding of the detrimental health effects of chronic exposure to aviation noise.

In conclusion, our experience with the introduction of a new runway at Dublin Airport has been disappointing. Communities have lost all trust in the airport authority’s ability to uphold its promises regarding any future expansion plans for the airport. Nevertheless, we offer the following suggestions to all airport authorities on how they could improve engagement with the communities around their airports:

- Present noise contours as maximum noise levels likely to be experienced, using single-mode representation, to accurately depict the real noise levels communities may expect.

- Noise contour maps should undergo more rigorous validation, preferably by an independent body separate from the airport authority, responsible for creating and validating the contours.

- The airport authority should hold public consultation events to present planned projects to the communities before any changes occur. This includes changes to flight procedures, expansion plans, and physical infrastructure plans. Town hall meetings where representatives from the airport authority present this information and answer questions should be mandatory.

- Noise mitigation contours should only be based on single-mode contours and should not include potential future reductions at source until those reductions are clearly validated through measurements. Communities should not carry the risk that noise reductions at source fail to materialize or where reductions in noise from individual aircraft are offset by overall increases in traffic.

- Noise monitoring should be conducted regularly to uphold noise contour validation and to investigate complaints effectively.

- Complaints should not be directed to the airport authority and instead, an independent body should be responsible for complaint management and investigation.

- Ongoing consultation regarding the operation of the airport and the impact on stakeholders, including community representation, should be mandatory.

- Airport authorities should be mandated to continually review mitigation measures and assess their impact significance based on the most up-to-date knowledge available.

Finally, we conclude by pointing out that the Balanced Approach to aircraft noise is not balanced and clearly favors the continued expansion of aviation.