Survey of Aircraft Noise Abatement Strategies in the US

By Eoin A. King & Paul E. Slaboch

Editor’s Note: This is a summary of an article originally published in the Noise Control Engineering Journal: King E.A, Slaboch P.E, Survey of aircraft noise abatement strategies in the US, Noise Control Engr. J. 71 (1), January-February 2023, copyright INCE-USA.

Introduction

Aircraft noise is generally considered one of the worst offenders among all environmental noise sources. It is often cited as a reason against airport expansion and is one of the most common complaints raised by residents living in the vicinity of airports [1]. Many different types of abatement measures can be utilized by airports to reduce the noise impact, but the manner of their implementation can vary between airports. To assess how noise control strategies are implemented across the United States, a national survey of noise abatement strategies was conducted.

This article provides a summary of this survey and reports the noise control approaches at 42 different airports across the United States. The survey considered general aspects of noise control, as well as specific questions related to noise abatement procedures, noise limits and curfews. Participants were also asked their opinion on the impact of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Balanced Approach, which is the ICAO recommended framework to address aircraft noise.

The Balanced Approach

The concept of a balanced approach to aircraft noise management was officially introduced by the ICAO in 2001 [2]. The ICAO Balanced Approach has at its core a theme of sustainable development of air travel without adversely affecting the acoustic environment. It identifies four key actions for noise control:

- the reduction of aircraft noise at source

- land-use planning and management

- noise abatement operational procedures

- operating restrictions.

Its goal is to address aircraft noise problems in the most cost-effective manner possible.

In the U.S., the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) formally accepted the ICAO guidance document on the Balanced Approach in an advisory circular in 2004 [3]. The FAA also requires each airport complete a 14 CFR §150 Noise Study (commonly referred to as FAR Part 150), which is a study prepared by an airport to define the five-year vision of compatibility between an airport and the surrounding communities. These regulations specify that airport operators must consider the aircraft noise and community noise around their regulated airfields. These planning documents guide much of the noise abatement procedures in the U.S.

This study aimed to assess how the balanced approach has been interpreted in the U.S. to determine whether it has influenced the adoption of different noise abatement strategies. With an understanding of what noise abatement strategies have been adopted, and whether or not U.S. airports adhere to the ICAO balanced approach, regulatory authorities can determine if a better approach to noise management could be implemented. To achieve this, a noise abatement survey was distributed to airport operators in the U.S.

Survey Method

The survey was hosted on SurveyMonkey.com, a web-based survey tool, that can collate responses once received, and allows individual responses to be downloaded for further analysis. Invitations were sent between January and February 2020, prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Airport operators were contacted via email addresses on file as well as through standard questionnaire boxes offered on individual airport websites. Having distributed the survey to approximately 300 airport operators, 42 responses were received. Most responses were received in February and early March, prior to travel restrictions related to the pandemic.

Table 1 lists airports from which responses were received, along with an overview of the daily operations, the number of operational runways and the location and distance from the city the airport is serving. Of these airports, seven are identified as Commercial Large Hubs as classified by the FAA included in the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS) for 2021-2025.

Table 1: Details of Airports Surveyed (details retrieved from [4]). Note: * indicates airport is a Commercial Large Hub.

| FAA Identifier | City Serving | Nearest City (miles) | Number of Runways | Daily Operations (approx.) |

| ABQ | ALBUQUERQUE, NM | 3 | 3 | 309 |

| AKR | AKRON, OH | 4 | 2 | 139 |

| ANC | ANCHORAGE, AK | 4 | 3 | 717 |

| BFI | BOEING-FIELD, SEATTLE, WA | 4 | 2 | 502 |

| BHM | BIRMINGHAM, AL | 4 | 2 | 287 |

| BNA | NASHVILLE, TN | 5 | 4 | 447 |

| BRL | BURLINGTON, IA | 2 | 2 | 55 |

| BUF | BUFFALO, NY | 5 | 2 | 132 |

| BZN | BOZEMAN, MT | 7 | 4 | 248 |

| CLT* | CHARLOTTE, NC | 5 | 4 | 1090 |

| CRP | CORPUS CHRISTI, TX | 5 | 2 | 230 |

| CVG | COVINGTON, KY | 8 | 4 | 322 |

| DAL | DALLAS, TX | 5 | 2 | 505 |

| DCA | WASHINGTON, DC | 3 | 3 | 816 |

| DEN* | DENVER, CO | 16 | 6 | 1212 |

| DFW* | DALLAS-FORT WORTH, TX | 12 | 7 | 1941 |

| EFD | HOUSTON, TX | 15 | 3 | 240 |

| FAI | FAIRBANKS, AK | 3 | 4 | 312 |

| GSO | GREENSBORO, NC | 7 | 3 | 181 |

| HPN | WHITE PLAINS, NY | 3 | 2 | 275 |

| HYA | HYANNIS, MA | 1 | 2 | 179 |

| IOW | IOWA CITY, IA | 2 | 2 | 53 |

| MCI | KANSAS CITY, MO | 15 | 3 | 197 |

| MCO* | ORLANDO, FL | 6 | 4 | 1003 |

| MIA* | MIAMI, FL | 8 | 4 | 1140 |

| MKE | MILWAUKEE, WI | 5 | 5 | 185 |

| OAK | OAKLAND, CA | 4 | 4 | 651 |

| OKC | OKLAHOMA CITY, OK | 6 | 4 | 240 |

| PBI | WEST PALM BEACH, FL | 3 | 3 | 306 |

| PDK | ATLANTA, GA | 8 | 3 | 442 |

| PDX | PORTLAND, OR | 4 | 3 | 309 |

| PIE | ST PETERSBURG-CLEARWATER, FL | 8 | 2 | 392 |

| PIT | PITTSBURGH, PA | 12 | 4 | 295 |

| PSP | PALM SPRINGS, CA | 2 | 2 | 157 |

| SDF | LOUISVILLE, KY | 4 | 3 | 414 |

| SEA* | SEATTLE, WA | 10 | 3 | 1233 |

| SLC* | SALT LAKE CITY, UT | 3 | 4 | 944 |

| STL | ST LOUIS, MO | 10 | 4 | 329 |

| SUA | STUART, FL | 1 | 3 | 330 |

| TEB | TETERBORO, NJ | 1 | 2 | 236 |

| TTN | TRENTON, NJ | 4 | 2 | 269 |

| TVC | TRAVERSE CITY, MI | 2 | 2 | 152 |

Survey Results

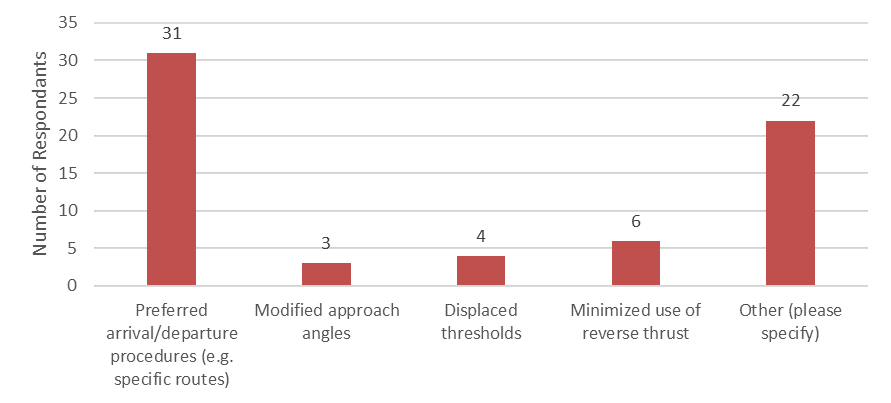

Figure 1 summarizes the types of noise abatement procedures implemented at each airport. Measures surveyed included the use of:

- preferred arrival/departure routes, which are generally used to ensure aircraft avoid flying over noise-sensitive areas in the vicinity of the airport

- modified approach angles, which can reduce the time an aircraft is flying at a lower altitude over a noise-sensitive area

- displaced thresholds, which involve moving the runway thresholds from the extremity of the runway surface end to a location further down the runway (away from a noise-sensitive area)

- minimized use of reverse thrust (the temporary diversion of an engine’s thrust), a procedure that is sometimes used to slow the aircraft on landing

- other.

The most popular procedure is the use of preferred arrival/departure routes at 74% of airports surveyed. The next most common approach is the minimized use of reverse thrust, but this is only applied at 14% of airports. The “Other” category received 22 responses, of these three reported the use of voluntary curfews during the nighttime, which varies between 22:00/23:00 and 06:00. The others included bespoke approaches including, for example, a home noise abatement program, sound attenuation construction requirements for residential development per city ordinance, and a two-minute limit on nighttime ground maintenance run-up.

Fig. 1: Survey responses indicating the types of noise abetment procedures at each airport.

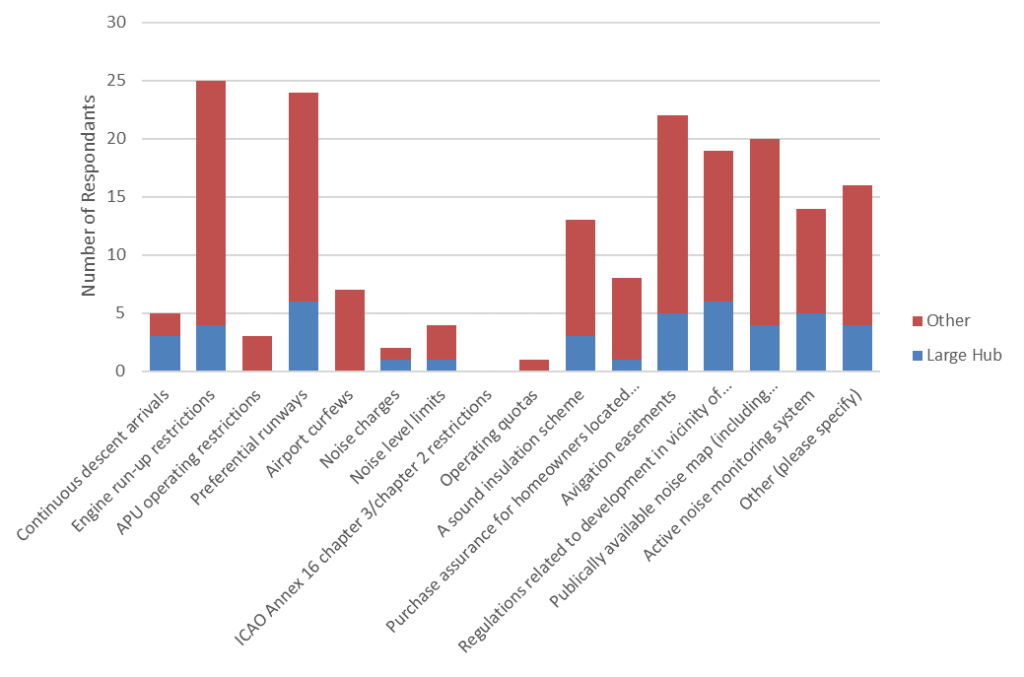

Figure 2 presents an extensive list of other noise considerations being implemented in the surveyed airports. Overall, it is quite evident that there is no single approach to noise control across the surveyed airports. The top five considerations include engine run-up restrictions (60% of airports surveyed), preferential runways (57%), avigation easements (53%), publicly available noise maps (47%), and regulations related to the development in vicinity of airports (45%). Eighteen airports considered both engine run-up restrictions, and preferential runways together. Only 1 airport surveyed imposes operating quotas, and only 2 airports impose noise charges. Two airports reported that none of the items listed in the figure are applied at their airport.

The analysis was then repeated using only the Commercial Large Hubs. With these airports a slightly higher level of consistency was observed. There were two specific actions that were implemented by 85% of these major airports; preferential runways and regulations related to development in the vicinity of the airport. Continuous descent arrivals are implemented in 3 of these major airports, and from Fig. 2, this means only 2 non-commercial hub airports surveyed implement this approach. No major airport implements noise curfews.

Fig. 2: Survey responses indicating range of noise related items in place at each airport (note for this analysis Commercial Large Hubs are identified).

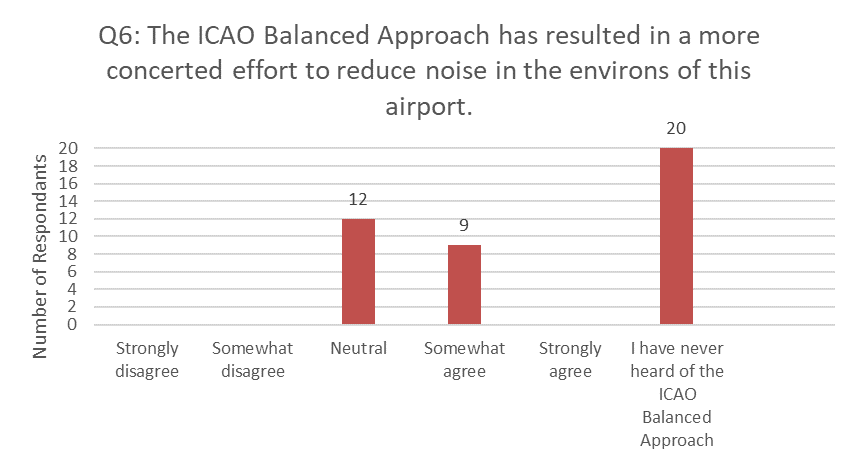

Figure 3 reports results on the general perception of the ICAO balanced approach across those surveyed. It shows that close to 50% of airport operators reported they were not familiar with the ICAO balanced approach. This could explain the lack of participation of some noise abatement procedures described above. Perhaps if airports were more aware of the ICAO balanced approach, they could be more open to mitigation tactics and implement them and reduce aircraft noise.

In the comments section of the survey, some airport operators explained that while they are familiar with the ICAO balanced approach, they follow a different noise abatement program as the “ICAO balanced approach is not standard”. Further, external factors can impede the implementation of noise abatement procedures. One response noted that the approach “requires input from multiple parties”, while another noted that “land-use planning and management is not always possible given local government, and operating restrictions are often impossible to implement”. Intergovernmental agreements may also restrict noise abatement procedures as compliance must be maintained. One response identified that land-use planning and management is very difficult to implement given some local government policies along with operating restrictions; “Local land use controls continue to be an issue as the demand for housing continues to increase while the remaining green space is proximate to the airport. Also, the U.S. cannot restrict aircraft operations so only three legs of the four legs of the ICAO stool are available”. Local land use jurisdictions seem to be unwilling to implement protective zoning against development of land near airports.

Fig. 3: Survey responses indicating attitudes to the ICAO balanced approach and its effectiveness.

Conclusions

Although just a snapshot of activities across the U.S. are presented, results indicate a wide array of noise abatement procedures are being implemented. Results also suggest that the ICAO Balanced Approach has yet to be fully embraced in the U.S., with a large proportion of respondents reporting that they are not familiar with this approach.

Further the study demonstrates that aircraft noise abatement is very much a local issue, with different approaches applied across the U.S. Additionally, there appears to be little consistency in the way noise limits and curfews are implemented. Finally, while it may be that a uniform approach to noise control across U.S airports is not appropriate due to varying local circumstances, and that such measures appear to be discouraged by the ICAO balanced approach, it seems that there is a need for uniform guidance on available measures.

References

- Murphy, E.A. King, “Environmental Noise Pollution: Noise Mapping, Public Health and Policy, 2nd Edition”, Elsevier, ISBN 9780128201008 (2022)

- Guarinoni, M., Ganzleben, C., Murphy, E., Jurkiewicz, K., “Towards a comprehensive noise strategy”, Policy Department Economic and Scientific Policy, European Parliament (2012)

- Federal Aviation Administration, Advisor Circular 150/5020-2, “Guidance on the balanced approach to noise management”, September 28, (2004).

- https://www.airnav.com accessed February 14, 2022.