How I Became a Noise Control Engineer

By Jim Thompson, PhD, PE, INCE Board Cert

For those who do not know me, I have worked in noise control my entire career of 46 years. I am now retired, but I still actively engage with INCE-USA. I have served as president and as vice president a few times, and currently, I am editor of the Noise Control Engineering Journal. I always enjoy hearing why people got into noise control. These stories tell me a lot about people when meeting them for the first time—or when talking to those who I have known for a long time! I hope you find my story interesting. I will confess that I also hope this short discussion helps to explain my passion for noise control and perhaps instills a little more passion about the profession in you.

When I was young, I developed a great interest in cars, particularly in automobile engines. In junior high school, I had books about engines and knew the specs for most US engines and many in European cars. I decided to get a degree in mechanical engineering and design engines as a profession. I knew this would require at least an MS and was committed to getting this degree before leaving school.

Unfortunately, I found out in my sophomore year that I would have to take courses in organic chemistry to understand combustion and be successful in engine design. This was a problem. I did not like chemistry, and my whole focus on engines had been on the mechanical side of things. My bubble bust. I did not see engine design as what I wanted to do anymore and was not excited about any other aspect of mechanical engineering.

To try to explore mechanical engineering and help pay for school, I entered the co-op program. I went to work for a small mechanical and electrical consulting firm in Baltimore. They did mostly HVAC and electrical design for institutional buildings. I started out as a draftsman. Yes, before CAD—drawing with pencil or ink on Mylar.

During my second semester assignment, the engineer responsible for the group in which I worked dropped about five books on my drawing table and said, “You are going to be our office noise expert,” and walked away. I had no knowledge of noise or acoustics—I was a sophomore student. Later, he sat down and explained that they had just gotten a project to design the mechanical and electrical systems for one of the Washington, DC, metro stations and the specs included stringent noise requirements. This was a big project for the company. His goal was for me to write a noise control manual for the office before my semester was up, to provide guidance on this project.

I should explain that my boss was from the inner city of Baltimore. While working at this firm, he put himself through the Johns Hopkins engineering program and rose from a draftsman to a principal engineer. He was no dummy, and he did not take no for an answer. When he walked in each morning looking at the rows of drafting tables, he would say, “I only want to see a––holes and elbows.” I had no choice but to become the office noise expert.

I worked for six weeks on only that manual, learning guidelines for noise emissions from motors, pumps, fans, ducts, lighting, ballast, and transformers. I gave my best attempt to write a manual, and for the first time, I had someone in the secretarial pool typing a document for me. (Yes, before there were computers on every desk.) My boss gave it back to me the next day. There was so much red on it, I thought he had cut himself. It took 10 iterations and the rest of the semester to get to a version he was willing to release. I knew my boss’s nature. The final version came when he asked if I thought it was ready for release and I said yes and would not back down when he said it was not.

Well, I went back to school interested in noise. I found out there was a senior technical elective noise control course. I also did my senior project on a noise problem in the auditorium in the continuing education center. To my surprise, there was a research project on the acoustics of industrial spaces where I could work on my MS.

Now I was ready to look for a job in noise control. There was only one problem: no one was offering me a job doing noise control. I talked to industrial and institutional design firms with no luck. I was convinced that building acoustics was what I wanted to do. Finally, on a fluke, I interviewed with a large chemical company. To my surprise, they got excited when I said I wanted to do noise control. They had an open position and could not find anyone to fill it. It was working on noise control to protect workers in chemical plants—not building acoustics, but it was noise control, nonetheless.

I worked there for five years and learned a great deal about noise control, dosimetry, audiology, people, and business. Then I went back to school for my PhD. Through a few stops and starts, I ended up working on noise from small engines. I was able to take my interest in noise control to a new level and decided I wanted a faculty position. When I graduated, I took a position in the mechanical engineering department at a major state university. I established myself and was working on several projects and had several graduate students.

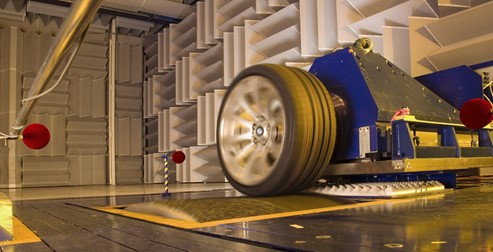

Then out of the blue came an offer from the world’s largest tire company. They had a new hemi-anechoic facility and needed to show its impact on the noise performance of their tires. It was an offer I could not refuse: an opportunity to get back into automotive doing noise control with great resources and support. To make a long story short, I stayed there for 12 years and worked with every major automotive manufacturer in the world. After this, I worked for several consultants mostly in automotive noise.

My final position before retirement was with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. There, I was chief of the Hearing Loss Prevention Branch. I was back to occupational noise. It was a great way to end my career—working to help people and being part of the government’s efforts to prevent hearing loss. This opportunity renewed my sense of service to people at large.

My passion for noise control can be summarized in the conversations I had with retired miners. Statistically, 80 percent of miners over 60 have significant hearing loss. This is much greater than the 10–15 percent that would be expected for those without extreme noise exposure. These are tough guys, and seeing them cry while telling me they could not communicate with their grandchildren was something I will never forget.

Whether it was chance or an innate interest in mechanical system dynamics, I went from a plan to do engine design to noise control. I have enjoyed my career in noise control. I have had the chance to participate in a many different aspects of the profession and maintain my childhood interest in cars. Along the way, I have developed a passion about the protection of hearing, and I do all that I can to make people aware of the need to do more. I can honestly say that I feel blessed to have had the opportunity to work in this profession and to have had a small part in making people’s lives better. I plan to continue to be involved in noise control, especially with INCE-USA, for as long as I can. I can only hope to have more opportunities to contribute to people’s quality of life and my chosen profession.

When I started my career, noise control was, at best, a necessary evil in engineering departments. Fortunately, it has now become a value adder for many products. The future of noise control is in sound management—not just reducing noise but also manipulating noise and sound to make it a positive. We have evolved from simply reducing noise to managing sound as part of the product experience or environment. There is an exciting future in noise control, with many innovations yet to come.