Lessons Learned from a Career in the Noise Control Industry, Part 2

By Jim Thompson

Some of you may have read the first part of this article in the previous NNI. As I stated in that article, sometimes I find it helpful to look at my experiences and try to derive some lessons learned from what has happened. One of my goals is to treat life as a continuous learning process. It takes some time to absorb some of what I have experienced and see how I can use it going forward.

What follows are some more of the lessons that have been meaningful to me. These are not strictly noise control issues, and in some cases they may not apply to others. I just thought they might be helpful or entertaining.

Unconventional Solutions Can Be Important

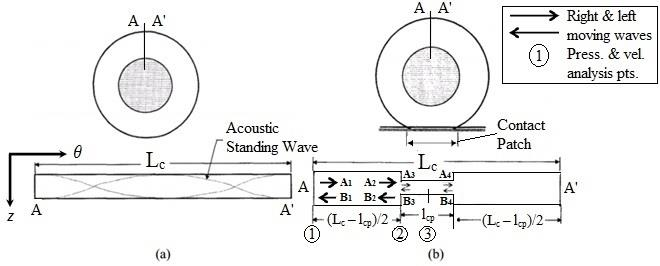

One of the tire noise contributors discovered while I was at Goodyear was the tire cavity resonance—a longitudinal acoustic resonance in the tire air cavity. This turned out to be an important source related to tire size and vehicle speed.

As cars got quieter and tire cross-sections got shorter, this resonance noise became more apparent at normal operating speeds. Since this noise was directly tied to basic tire geometry, we did not have many real solutions. At one point, one of our engineers tried stuffing bubble wrap in the tire cavity and found it was enough to prevent the resonance. I dismissed this as a waste of time since it could not be used in real operation.

A few months after this, I was having lunch in my office when I got a call from an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) engineer. He had a VP coming to ride his prototype that had a cavity resonance noise problem. He was concerned that the VP was going to reject the vehicle for noise. He had less than an hour and needed a miracle to save his program. He had talked to our sales representative and was assured I would have an easy solution. In this one case, it turned out to be true.

So, I told him to put bubble wrap in the tires. After a great deal of skepticism, he agreed he had no choice. The result was that I had a friend for life. I learned that you never know when a stupid solution is suddenly going to seem brilliant. I did go back and apologize to the engineer who came up with the idea in the first place. The bad news was that the sales representative assumed I could solve every problem that easily from that point on.

It Is Critical to be Able to Speak to a Hostile Audience

Too many of us go through school and even work experience never really speaking to a hostile audience. Maybe your boss in not receptive to your idea, or your major professor does not agree with your results. This is not hostile. This is a professional disagreement. Speaking to a truly hostile audience is a whole other experience.

A few times I have had to speak to hostile audiences about environmental noise studies that did not agree with the community’s opinions. In some cases, customers are not happy with the results from a consulting program or the cost and complexity of a solution. I have found handling these situations professionally and not getting caught up in the emotion can be difficult. Here is the acid case that tested my abilities and turned out to be a great success when all was done. I was working as a consultant, and a brake friction material supplier came to us. Their material was on a new vehicle that had a unique noise problem. There was a groaning noise after a stop. The OEM and foundation brake supplier were blaming them for the noise problem. They had investigated the noise and could not understand what was causing the problem. They needed our help and hoped we could show that their friction material was not the source of the problem.

This turned out to be a difficult problem to replicate. The noise only occurred when the vehicle was pulling away from a stop. Yes, that is right, a brake noise problem that only occurs when the brakes are released. In the simplest terms, the noise occurred when the brake system was at high temperatures and the vehicle came to a slow stop. There was some stiction between the brake pad and the rotor. When the vehicle pulled away from the stop, there was a sudden release that excited a resonance in the caliper. The vehicle passengers heard a strong moaning noise that only lasted a few seconds, but it was clearly audible and could be a source of concern.

Once we were able to recreate the problem, we understood the caliper resonance and could see how the problem might be resolved. We provided a demonstration for the friction material supplier, and they were delighted with our results. They scheduled a meeting with the OEM and the foundation brake supplier for us to present our findings. At this point it all seemed straightforward to me.

A couple of days before the presentation, I learned that the brake engineer from the OEM was an individual with a bad reputation. He was infamous for chewing up and spitting out suppliers. He had a bad temper and felt his role was to abuse suppliers at every opportunity. This was the guy who would make brake purchasing recommendations and supplier decisions. As the friction supplier put it, he could make a “life or death” decision.

I had planned to have some of the junior engineers who participated in the test to be part of the presentation. They all begged to not be asked to stand up and present to this gentleman. Their immediate supervisor advised me it would not be good to have them to be a part of the presentation. He was afraid they could not take the abuse well and would make poor presentations. So, it all fell to me.

Knowing all of this, I tried to prepare a short presentation that was to the point that showed both the problem and a potential solution. When all gathered in the conference room, the OEM engineer stated to all present that this meeting was a waste of everyone’s time because the problem was clearly the friction supplier. I had gotten to the second slide when the OEM engineer interrupted me to tell me again that I was wasting his time. I took a chance and told him he was wrong and if he would let me continue that I would explain the real problem. To my surprise, he sat down and said “OK, show me.” I should say this was uttered with less than a positive attitude. I got about two-thirds through the presentation, and he stopped me. He stood up and said “So, the problem is the caliper.” He turned to the foundation brake supplier and asked if they had seen this problem before. To everyone’s surprise, they said yes.

Leaving out the expletives used by the OEM engineer, we then began to discuss the real problem. The OEM engineer told the foundation brake supplier they had a month to solve the problem. In addition, he demanded that they pay our fees even though the friction supplier had contracted the work. He then walked out of the room. I never got to finish my presentation.

In the end, the foundation brake supplier paid for our original work and another month to come up with a solution. The friction supplier thought I was a god—until the next project when we wanted money to do the work. If I had not handled the hostile OEM engineer well, this would have been a disaster. I did what I thought was best at the time and did not get intimidated. I also had a very well-prepared, logical, and succinct story to tell. I was happy with the result even though I never got through my whole presentation. The lesson I learned is know your audience and when they are hostile, be prepared for it. Knowing when to hold your ground and when not is essential. Above all, you must always stay professional even when the most important person in the audience is hostile to you and what you are trying to say.

Good Work May be Slow to be Acknowledged

My MS project was focused on modifying the room acoustics equation to better predict sound in factory spaces that are not regularly proportioned rectangular shapes. Because of contract issues, I had to work as a teaching assistant for funding, and the project did not have funding for experimental work. I was doing measurements in irregularly shaped classrooms: removing and replacing a hundred desks at 3:00 a.m. in the morning to try to get the experimental data I needed without running up costs. When funding was received, all the enthusiasm was behind building a ray tracing model to predict noise in these spaces. I finished my thesis and left school with a bad taste in my mouth. I felt what I did was good work that was underappreciated.

I never really got back to building acoustics again, but I stayed interested. At a recent INTER-NOISE conference, there was a session on industrial room acoustics that looked interesting. I was running from another session and got there a little late. The presenter was talking about the different methods he had used to predict noise in several factory spaces. Then he summarized the findings noting that the best predictor was the equation from Thompson. I had missed the part where he reviewed my work. Silly as it may seem after 40 years, I walked out of that session with a smile on my face. Sometimes there is a long delay before your good work is recognized. Probably I was too sensitive about my work not being appreciated, but it sure felt nice to find out over 40 years later that someone still found it useful.

Conclusions

I hope these lessons learned have been helpful and perhaps a little entertaining. I have enjoyed sharing them. Please remember that life is a learning process and drawing lessons learned as you go along can be helpful. I have many more of these, but I think I have shared enough for now. Maybe the most important lesson learned is to keep learning lessons and be open to life’s educational process.