Lessons Learned from a Career in the Noise Control Industry—Part 1

By Jim Thompson

I hope this article is not too presumptuous. Often, I find it helpful to look at my experiences and try to derive some lessons from them. One of my goals is to treat life as a continuous learning process. It helps to allow some time between events before trying to define the lessons learned. A little perspective allows me to absorb some of what I have experienced and see how I can use it going forward.

What follows are some of lessons that have been meaningful to me. These are not strictly noise control issues, and they may not apply to everyone. But I think they might be helpful—or at least entertaining—to others.

Honesty Is (Often) the Best Policy

I know this is trite and is not strictly true. There are cases where it is better to hold one’s tongue—to keep from embarrassing someone or making others uncomfortable, or if it is not the right time or place. A better lesson would be “When You Have No Other Way Out, Honesty Is the Best Policy.” The only way to explain is to provide a couple of examples.

Early in my time with a major tire company, I was asked to go with our sales representative to a Japanese original equipment manufacturer’s (OEM) development center in the Detroit area. They had a sports car that had our high-performance tires on it. They claimed to have found a competitor’s tire that was much quieter.

We were introduced to about a dozen people. Several of them did not speak English, or so we were told. We rode two cars, one with our tires and one with the competitor’s tires, on a stretch of highway near their offices. The competitor’s tire was a regular passenger tire with a fancy sidewall to try to make it look like a high-performance tire. Based on our rides, we concluded our tire was roughly 3 dB noisier. When we reconvened in their conference room, I reported this difference, which closely matched what the OEM had found in their testing.

Our salesperson talked about our long relationship, our high-performance tire’s excellent reputation, and so on. This did not seem to be working. Out of naiveté and maybe a little frustration, I asked if I could talk about the performance difference. I noted that the competitor tire was not really a high-performance tire. I explained that when I was driving, there was a 10-miles-per-hour difference in the speed on the on-ramp to the highway we had used for the test rides. I went even further, saying I knew of no tire of equal performance that was significantly quieter than ours. At this point, our salesperson did not seem entirely pleased with me. The OEM personnel were talking among themselves as well.

One of the Japanese engineers waved over a technician and talked with him quietly. The technician then ran out of the room. We went on talking about tire alternatives and business. I was worried I had just made the customer mad. I was wondering if I should start working on my résumé or buy the sales guy a few beers when we left.

In about 20 minutes, the technician came back in the room and whispered to the engineer, who again sent him out. I found out later this Japanese gentleman was the program executive from Japan and the real decision maker. After he talked to the technician, he turned to me and, in perfect English, said, “Nine miles per hour.”

The meeting was shortly wrapped up, and we kept the business. I was relieved that I had not blown the situation. Probably I should not have blurted this out. However, I felt like we were going to lose the business unless I said something.

Several years later, I was still working for the tire company, and a different sort of situation came up that forced me to decide to be completely honest. Early in a new vehicle development program, I was asked to go to Japan to ride a Japanese company’s mule (a current model car with a chassis and components for the new car installed on it). The principal objective was to discuss their noise goals. We had submitted our first set of development tires that we would be riding. The indications were that they were not entirely happy with the noise performance. This was a very prestigious program, and a lot of people were concerned. This concern went several levels above my pay grade, and I received a lot of input about the importance of this program.

Four of us went for this meeting. This included me and three salespersons from both the United States and Japan. A ride with two vehicles on a public road was arranged. Without my realizing it, the customers managed to put me in a car with only the OEM engineers. Later, I found out they were the NVH (noise, vibration, and harshness—an old automotive term) development team.

We drove on surface streets and a highway and stopped at a rest area. As soon as we got out of the car, the OEM engineers surrounded me and asked what I thought about the tire noise. I had no one from the sales team to help me. I decided I should be honest but knew my response was not positive. With a lot of concern, I told them I could not hear the tire noise over the transmission whine.

Two of the three engineers almost fell down; they were laughing so hard. From broken English, I learned this was what they had been trying to tell their boss for several weeks. They treated me like a colleague from that point on. When the car with the sales team arrived, they got concerned because the OEM team all went off by themselves to talk. When I told our sales team what I had said, they really got upset. I was told in no uncertain terms that I should never find fault with the Japanese OEM’s vehicles.

It turned out fine, and we got exclusive business on what became the Lexus LS 400, heralded as the quietest car in the world when it was introduced.

So, is honesty always the best policy? Certainly, there are many cases when it is. There are also cases where one is better off keeping quiet. One of the important aspects to honesty is the best policy is to be sure you understand the situation and know what you are talking about. If I talked about excessive transmission noise or speeds in turns without knowing what I was talking about, these two cases could have been a disaster.

Do Not Argue with the Person Who Has Already Made Up His or Her Mind

This is the opposite side of honesty is the best policy. There are times when it is better not to be honest if it means being argumentative.

From an early boss, I learned this phrase: “Do not argue with the person who has made up his or her mind.” He had a few sayings like this, and besides being humorous, they had wisdom behind them. They were good guidelines in dealing with people. Many times, they have provided guidance, and in a few cases they have saved me from major screw-ups. Most of his sayings were about what not to do. There were not too many of them about what to do, for some reason.

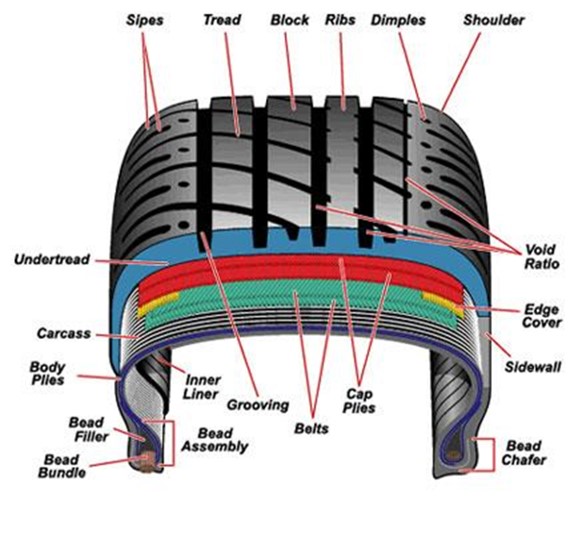

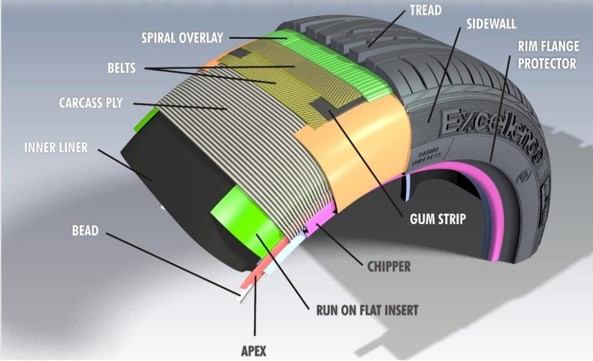

Again, working at the tire company, I was in a meeting with the light truck group when they announced they were changing the pitch sequences on all their tires. For those not familiar with tires, the size, circumferential length of tread elements, are varied in a sequence to randomize the spectrum and avoid strong spectral peaks. We had an effective sequence, and I knew what they were doing was going to make their tires much noisier.

I was getting materials ready to go to the light truck product manager and show him the error in his ways. My boss stopped me and taught me this rule. I kept wanting to go and have this discussion, and he kept telling me no. He made the clear point that the decision was made, and my actions could, and probably would, be seen negatively. I reluctantly agreed, thinking this was a mistake.

They changed all their pitch sequences, the tires got much noisier, and in less than a year, the group changed back to the old pitch sequences. I never had to say I told you so, and the group was much more receptive to my input than before.

If I had argued with them, they would have resented my contradiction and would still be resistant to my input. It cost the company some money, in the millions of dollars, but saved the company many more millions in the long run. The light truck manager and I went on to be good friends. Clearly there was risk in not responding honestly. If I had looked at this from a purely technical point of view, I would have responded negatively. My boss’s wisdom was to understand that we were dealing with people, not engineering facts. This was a hard lesson for me to learn, but looking back on my career, it has been an invaluable one.

Competitors Are Not Always Right—or Smarter Than You

In many cases, I found upper management eager to believe the competition knew more or was smarter than their own engineering team. Too many times, I have heard “Company X does this differently. They must know something we don’t.”

I ran into a similar sentiment at the tire company. We used a nylon layer over the belt package to give high-speed performance. Nylon was expensive and had some other issues. Management wanted to get rid of it, but we could not find a way. The nylon layer provided structural reinforcement and shifted the natural frequency higher to permit higher speeds.

Our major competitor in Europe—they should have known a lot about high-speed performance, with unlimited speed highways at the time—was only using nylon strips at the belt edge to shoulder area. I got several notes and questions from my VP, inferring the competitor knew more than we did, and we must be inept. If this competitor was taking this approach, we had to be stupid and wrong.

We did countless analyses with FEA and modal models to show that our approach was better. I made multiple presentations to my VP and the board of directors about our approach. Still I kept getting questions in meetings and in the hallway and notes asking what we were missing. At one point, my VP threatened to bring in an outside consultant. I said that would be fine and that it would only take us a year to teach them enough about tires to understand the problem. I am not sure this was believed, but no consultant was brought in.

This went on for about three years. Then our competitor advertised in magazines and trade journals that they had made a breakthrough in their tire designs by going to a full nylon overlay. This was essentially the same construction we had been using. Of course, it was a stunning technical innovation in their announcement. I sent a copy of this announcement to my VP, and he never mentioned that I had been right all along. I got no pat on the back—or any acknowledgment whatsoever. Later, I found out that the engineers at the competitor had been telling their bosses that our approach was better, and we could not get them to change the traditional design.

The point is not that we were right. We could have been wrong. The point was that the competitor was not automatically right. We devoted a lot of time and effort evaluating our approach against theirs, coming at it from various angles. For three years, we stood by our guns, hoping we had not missed something. When the announcement from the competitor came, we did have a small celebration in the engineering group.

Conclusions

I hope these lessons learned were interesting. I have more I want to pass along, so look forward to part 2 of this feature. If nothing else, please take away the concept that life is an educational process, and taking the time to reflect on what you have learned can be helpful. It has been invaluable to me.